This kind of exposure is critical to the boys’ development of a healthy sense of self and agency.

This is the second of two articles discussing ways teachers can make their classrooms more welcoming and supportive learning spaces for Black boys. The first article, “Black Boys Matter: Cultivating Their Identity, Agency, and Voice,” was published in the Feb/March 2019 issue of TYC.

In American classrooms—including preschool classrooms—studies show that Black boys are more likely to be seen as “problem” children than their peers, and they are less likely to be considered ready for school. For example, a Yale Child Center study found that preschool teachers spent more time watching Black children than White children when looking for disruptive behaviors. Proactive, culturally competent teachers can work to counter these misperceptions and create classroom environments where Black boys feel welcome to learn, dream, and be themselves.

In my previous article, I focused on how teachers can identify and begin addressing unconscious biases about Black boys through self-reflection. Here, I offer teachers practical suggestions to help them foster Black boys’ positive identity development, promote agency, and voice, and create conditions that will empower Black boys to succeed in school.

A culturally responsive, strengths-based approach

It is important that teachers focus on what Black boys know, understand, and can do (as opposed to what they cannot do or what they do not know or understand). Culturally responsive, strengths-based teachers do not engage Black boys from a deficit perspective (i.e., having “problems to fix” or being “at risk”). Instead, they seek to learn about Black boys’ strengths, gifts, and talents.

Three ways teachers can take this approach are by tapping into the power of history, celebrating Black boys in books, and rethinking school readiness.

Tapping into the power of history

Culturally responsive teachers work to affirm Black boys’ experiences through the content of their lesson plans. They incorporate books, visuals, and other materials that reflect Black histories, lives, and points of view.

For example, many preschool teachers use the concept of “history and me,” which celebrates the richness of African American history and the roles Black boys and men have played in bringing about social change through taking a stand for social justice and equity. When teachers embed a “history and me” perspective within the social studies curriculum, they also create opportunities to emphasize current examples of Black boys and men as valuable community members.

This kind of exposure is critical to the boys’ development of a healthy sense of self and agency. Learning about the important discoveries and courageous acts of Black boys and men from the past and present can serve as an important reminder for today’s Black boys to see themselves and their communities as vital parts of American history. It also empowers them to challenge the “troublemaker” and “bad boy” stereotypes found in typical portrayals of Black boys.

Reading and discussing carefully selected picture books is a great way to incorporate “history and me” into preschool classrooms. For example, the biographical account Richard Wright and the Library Card, written by William Miller, and historical fiction such as Sit-In: How Four Friends Stood Up by Sitting Down, written by Andrea Davis Pinkney, show Black boys how young people like them have accomplished great things.

Preaching to the Chickens: The Story of Young John Lewis, written by Jabari Asim, is another great real-life story. It shows how John Lewis—long before he became a Freedom Rider and US congressional representative—used play to imagine and then act out his dream of becoming a preacher and inspiring people to improve their lives. In addition to reading aloud Preaching to the Chickens and discussing Lewis’s life, teachers may want to add materials to their dramatic play centers to help children imagine and act out their dreams.

Other books to consider for developing a “history and me” approach include Freedom Summer, written by Deborah Wiles, and Delivering Justice: W.W. Law and the Fight for Civil Rights, written by Jim Haskins. Both show young African American men using their agency to challenge racial discrimination in the South.

Although the focus of this article is Black boys, it’s worth noting that seeing the accomplishments of Black men and boys through these stories also helps children from different racial and ethnic groups. Through a thoughtfully planned read aloud, critical discussions, and related classroom activities, all children can come to understand that the cultural stereotypes they may have absorbed about Black boys are myths.

Celebrating Black boys in books

Much like history and social studies books, carefully selected, authentic multicultural children’s books can also introduce Black boys to mentors on paper. Black boys, perhaps more than any other group of children, need access to what Rudine Sims Bishop calls “mirror” books—books that reflect themselves, their families, and their communities in positive ways. Currently, there are far more “window” books—books that give Black children a glimpse into the lives of other people (mainly the White world)—than mirror books showing their own communities. These mirror books highlight cultural histories, music, the arts, language varieties, fashion, cuisine, and other culturally rich experiences found in Black communities to engage Black boys.

Here are some picture books that feature Black boys facing the kinds of situations children might see in their everyday lives.

- In Riley Knows He Can and Riley Can Be Anything, written by Davina Hamilton, Riley first overcomes his stage fright to play a wise king in the class play and then imagines the many possible careers he might have.

- Derrick Barnes’s Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut celebrates the Black barbershop as a place that can transform a boy into the stylish king of his neighborhood.

- Combining the “history and me” and mirror approaches, Hey Black Child, written by Useni Eugene Perkins, and Dad, Who Will I Be?, written by G. Todd Taylor, use words and visuals to introduce readers to important people and events from African American history and encourage Black boys to pursue their dreams

Seeing characters like themselves in these books can help Black boys develop a stronger sense of themselves, including their abilities to pursue their goals and tell their own stories.

Rethinking school readiness

Culturally responsive classrooms honor and value the cultural and personal identities of all children, and Black boys in particular. One area in which this can be challenging is typical measures of readiness for kindergarten. Teachers can avoid the effects of unconscious biases by taking a strengths-based approach to readiness.

One common indicator of kindergarten readiness is how long a child can sit quietly in a classroom. Sustained periods of quiet sitting may be helpful from a classroom management perspective, but they do not reflect what we know about the importance of movement in learning. In addition, long periods of quiet sitting undermine children’s verve. The term verve is often used to describe energy and spirit in the arts; in education, it refers to having high levels of energy—being physically active and “loud”—when mentally stimulated. Verve is a great description of how many Black boys behave when they are excited about learning. With the concept of verve in mind, culturally responsive teachers can encourage indoor and outdoor large-motor and whole-body experiences, such as by putting mats in spacious areas to encourage Black boys—and all children—to tumble and roll.

Another common indicator of readiness is how well children follow rules. The ability to meet school and classroom expectations is considered good behavior. While following rules can ensure safety and help children understand what is expected in a particular setting, teachers should consider whether the rules are stifling children’s expressive individualism. Black boys, and other children, benefit from being creative and taking risks as they explore, experiment, and follow where their curiosity leads them. Knowing this, culturally responsive teachers are flexible in the ways they interpret “good behavior.” They reflect on children’s reasons for not following rules and create opportunities for spontaneous, ongoing exploration of “What if…?” questions.

Culturally responsive, strengths-based teachers also consider the implicit bias of some kindergarten readiness indicators like obeying instructions without questioning or challenging authority figures (compliant behavior). This expectation of quiet obedience clashes with the oral cultural practices of many African Americans; it may also hinder their pursuit of fairness, equity, and consistency in their education. A blunt and direct communication style may be perceived by some teachers as rude or a sign of a “bad” or “disrespectful” child. In contrast, culturally responsive teachers acknowledge children’s cultural heritages as legacies that affect dispositions and attitudes. These teachers understand that Black boys’ questions are indications of engagement, curiosity, and brilliance that are worthy of addressing in the classroom.

Conclusion

As with all children, the social and emotional well-being of Black boys must be our highest priority. Making sure we see them, hear them, and know them is the starting place for providing them with schooling that is humane, culturally responsive, equitable, and strengths-based. Culturally responsive practices and strategies, like those discussed here, support and promote Black boys’ positive identity development, agency, and voice inside and outside of school. This is what we should strive for as early childhood education professionals. Our Black boys matter, and they need, want, and deserve nothing less.

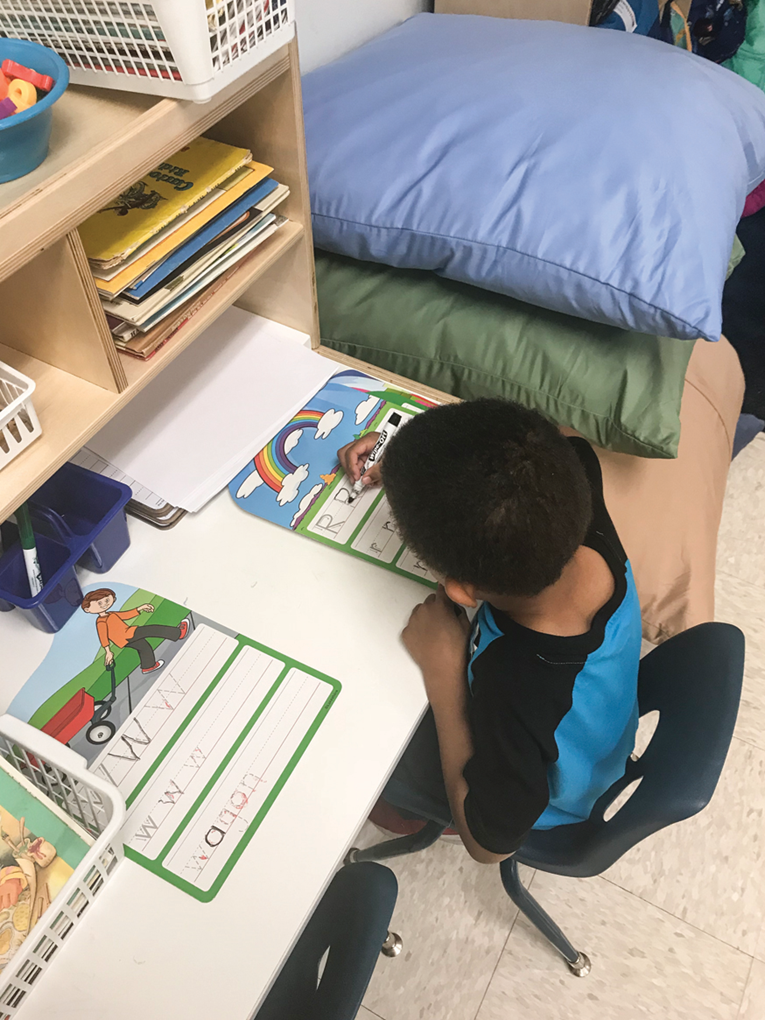

Photographs: Courtesy of Shelby County Schools Division of Early Childhood Education and the Barbara K. Lipman Early Childhood School and Research Institute at the University of Memphis

Brian L. Wright, PhD, is an assistant professor and coordinator of the early childhood education program at the University of Memphis. For a more thorough exploration of how teachers can nurture the Black boys in their classes, see The Brilliance of Black Boys: Cultivating School Success in the Early Grades, with contributions by Shelly L. Counsell.