Attacking the Black–White Opportunity Gap That Comes from Residential Segregation

KIMBERLY QUICK AND RICHARD D. KAHLENBERG

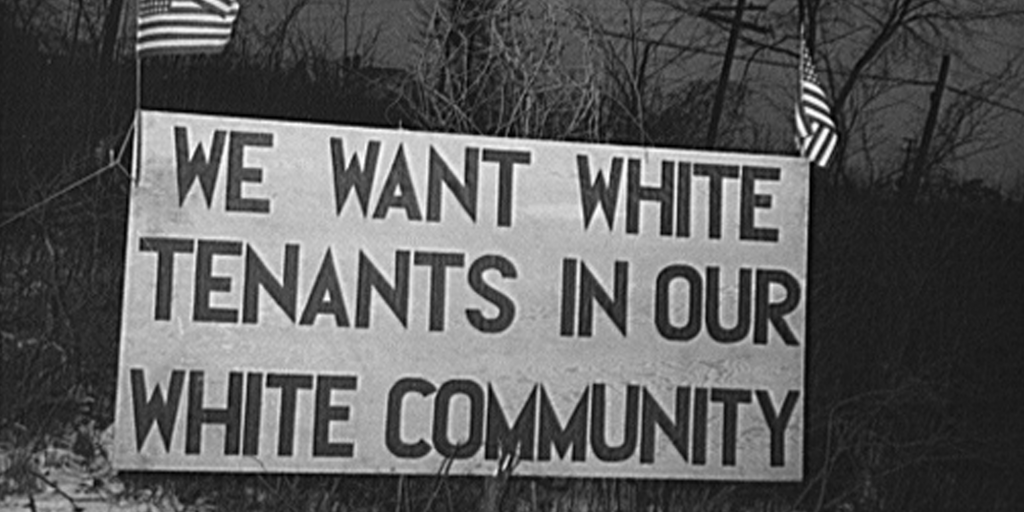

Residential segregation between black and white Americans remains both strikingly high and deeply troubling. Black–white residential segregation is a major source of unequal opportunity for African Americans: among other things, it perpetuates an enormous wealth gap and excludes black students from many high-performing schools. While some see residential segregation as “natural”—an outgrowth of the belief that birds of a feather flock together—black–white segregation in America is mostly a result of deliberate public policies that were designed to subjugate black people and promote white supremacy.

Because the federal, state, and local policy arenas were the laboratory for engineering black–white residential segregation, that is where people must work to help undo it. In order for these heinous differences to be reversed, people in government at all levels have to be proactive in eliminating policy that supports segregation and in creating anti-segregation policies.

It is time for bold action. The first part of this report outlines why all Americans should care about black–white residential segregation: the perpetuation of an opportunity gap between blacks and whites. The second part delineates the ways in which black–white segregation is rooted primarily in deliberate government policies enacted over generations. And the last part of the report sketches a four-prong strategy for undoing this horrible creation.

First, policymakers should address the legacy of generations of racial discrimination in housing by implementing the “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing” provision of the Fair Housing Act and providing new mortgage assistance to buy homes in formerly “redlined” areas. Second, government should seek to reduce contemporary residential racial discrimination by increasing resources allocated to fair housing testers and reestablishing the federal interagency task force to combat lending discrimination. Third, officials should counter contemporary residential economic discrimination that disproportionately hurts African Americans by curbing exclusionary zoning, funding “disparate impact” litigation, adopting “inclusionary zoning” policies, banning source of income discrimination, and beefing up housing mobility programs. Fourth, policy officials should respond to the re-segregating effects of displacement that can come with gentrification by revising tax abatement policies that promote gentrification, implementing longtime owner occupancy programs, and investing in people, not powerbrokers.

How Black–White Segregation Perpetuates an Opportunity Gap

Residential segregation between black and white Americans remains very high more than fifty years after passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. An analysis of U.S. Census Data from 2013–17 found that the “dissimilarity index” between blacks and non-Hispanic whites for metropolitan areas was 0.526 for the median area—meaning that 52.6 percent of African Americans or whites would have to move for the area to be fully integrated. (A dissimilarity index of 0 represents complete integration between two groups, while 100 represents absolute apartheid.) The index for black–white segregation was higher than it was for segregation between non-Hispanic whites and Asians (0.467), and segregation between non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics (0.407).1 And while the nation is also seeing increasing residential segregation by income, racial segregation today remains starker and more pervasive than economic segregation.2 Analyzing data over time, Paul Jargowsky of Rutgers University writes of African Americans: “Few groups in American history have ever experienced such high levels of segregation, let alone sustained them over decades.”3

Residential segregation matters immensely, because where people live affects so much of their lives, such as their access to transportation, education, employment opportunities, and good health care. In the case of black–white segregation in particular, the separateness of African-American families and white families has contributed significantly to two entrenched inequalities that are especially glaring: the enormous wealth gap between these races, and their grossly unequal access to strong public educational opportunities.

WHITE TENANTS SEEKING TO PREVENT BLACKS FROM MOVING INTO THE SOJOURNER TRUTH HOUSING PROJECT ERECTED THIS SIGN IN DETROIT, 1942. SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

It is well established that historical and contemporary racial discrimination has given rise to a substantial income gap between black and white Americans. African Americans make, on average, about 60 percent of what whites make.4 But housing segregation helps explain the ways in which African-American families are further disadvantaged compared to white families who have the same income and education levels. Typically, higher levels of education and income translate into higher levels of wealth and less exposure to concentrated poverty. In the case of African Americans, however, residential segregation by race imposes a penalty that interrupts these positive patterns. Stunningly, African-American households headed by an individual with a bachelor’s degree have just two-thirds of the wealth, on average, of white households headed by an individual who lacks a high school degree.5 Equally astonishingly, middle-class blacks live in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates than low-income whites.6 As the following sections will show, these negative outcomes are largely a result of residential segregation; furthermore, when black–white segregation is reduced, outcomes for black families are shown to improve.

How Residential Segregation Affects Wealth Accumulation

Racial residential segregation inhibits home value appreciation in predominantly African-American neighborhoods. Research finds that some white families remain distressingly resistant to buying homes in predominantly African-American neighborhoods; for example, even when all other characteristics of homes and neighborhoods are identical, white respondents view predominantly black neighborhoods as less safe and less desirable than predominantly white neighborhoods.7 Fewer potential buyers—particularly among the whiter and thus usually wealthier segment of the market—means significantly lower rates of home appreciation.

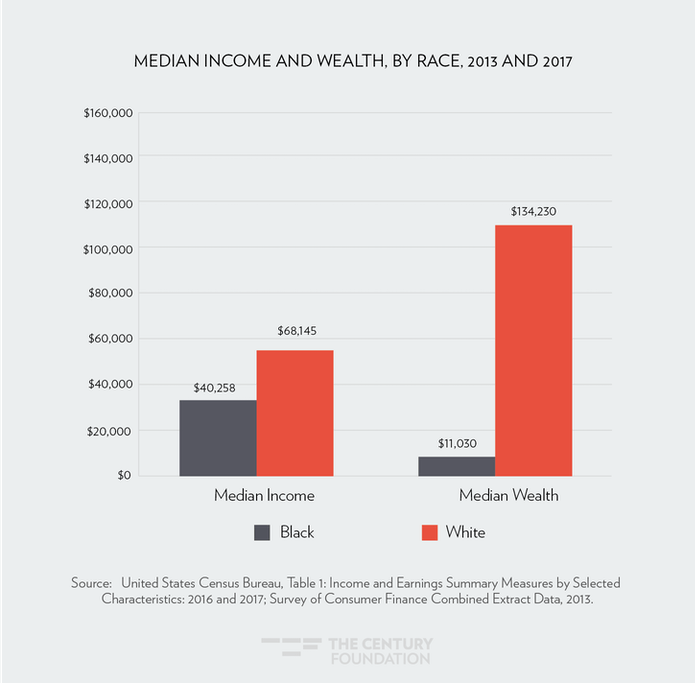

Because homes are typically the largest financial asset for most Americans, segregated markets significantly reduce the accumulated wealth of blacks. This phenomenon—on top of the penalties endured during the historical legacy of slavery and Jim Crow—helps explain why the black–white wealth gap is so much larger than the black–white income gap. While median income for black households is 59 percent that of white households, black median household net worth is just 8 percent of white median household net worth.8 (See Figure 1.)

FIGURE 1

The segregation-driven wealth gap imposes enormous burdens on African Americans. Having or lacking wealth influences many of life’s big decisions—from financing a child’s education to saving for retirement.