Research shows that African American students with higher quality student–teacher relationships scored higher on achievement tests compared to African American students with lower quality relationships

A Sense of Mattering: A Group Intervention for African American Boys

Eva M. Gibson, Mariama Cook Sandifer, Winifred Bedford

Abstract

African American boys have been disproportionately represented in school discipline data. School counselors are encouraged to integrate cultural considerations while developing interventions for African American boys. A middle school counselor (the first author) utilized discipline data to create a culturally responsive group intervention designed to affect behavior and develop social/emotional skills. Through the analysis of perception and outcome data, findings indicated improvement in behavior and social/emotional skills among participants. We discuss implications for school counselors, school counselor education programs, and school districts.

Keywords African American male students, at risk, group interventions, social/emotional

African American boys have been disproportionately represented in school discipline data. Consequently, literature reflects evidence of higher levels of punishment for this population (McKenna, 2013; Taylor & Brown, 2013; Vincent & Tobin, 2012). Despite the fair amount of scholarly materials that explore these inequities and propose solutions, simply acknowledging these disparities is not enough. A greater examination of the impact of specific interventions for African American boys is needed (Miranda, Webb, Brigman, & Peluso, 2007). As educators work to bridge gaps, they often do not utilize school counselors appropriately, but if school counselors are allowed to take on appropriate duties, they can impact change in a meaningful way (Shimoni & Greenberger, 2014).

School counselors serve an important role in enhancing student success and are uniquely qualified to address the social/emotional needs of all students (American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2012b). School counselors’ demonstration of the effectiveness of interventions is important in this era of evidence-based practices (Whiston, Tai, Rahardja, & Eder, 2011). As they enter the workforce, school counselors are encouraged to adopt a transformative paradigm to help improve student success rates (Dahir & Stone, 2006). This paradigm includes a focus on social justice, equitable access, and the examination of data to inform decisions achieved through the implementation of comprehensive school counseling programs (ASCA, 2012a) and targeted behavior interventions. A particular need is for counselors to review data to effectively plan and assess targeted interventions connected to this linkage (Bemak, Williams, & Chung, 2014). In the present study, a middle school counselor implemented a small-group intervention for African American boys, designed to improve behavior and develop social/emotional skills.

Literature Review

School counselors can have a positive impact on social/emotional development by providing small-group counseling interventions. In a study by Amati, Thompson, Rankin-Clemons, and Ettinger (2010), a small group focused on families of students with attention and aggression problems. The participants met on a weekly basis for a duration of 6 weeks, and the group was successful in improving the targeted behaviors. Rose and Steen (2014) focused on enhancing interpersonal skills and resiliency in minority students. After eight group sessions, students felt empowered to apply skills learned throughout the process. Ohrt, Webster, and De La Garza (2014) utilized a group counseling approach with at-risk students and found that it enhanced self-regulation and perceived competence. Furthermore, behavior has been linked to academic success. Miranda, Webb, Brigman, and Peluso (2007) provided a relevant illustration of this relationship: The researchers implemented a group to develop cognitive, social, and self-management skills through classroom lessons and group interventions. Results proved a positive connection between development of the targeted sets of skills and achievement.

Despite successful interventions, school performance gaps between African American students and their White peers continue to exist. African American students, although they represent less than 17% of the school population, are more likely to be retained than any other group (National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). Group counseling has proven to be effective in reducing academic performance gaps (Davis, Davis, & Mobley, 2013; Miranda et al., 2007; Rose & Steen, 2014). One study on the impact of group counseling on African American students’ testing achievement included weekly sessions focused on school success skills, strategies, and behaviors and found that academic performance improved after the intervention (Bruce, Getch, & Ziomek-Daigle, 2009).

Group counseling has also been effective in supporting minority students in high achievement programs (e.g., gifted, talented, advanced placement). In an effort to challenge systematic barriers and address opportunity disparities, researchers provided group counseling for African American students in an advanced placement program (Davis et al., 2013). The sessions focused on creating a community of achievement, increasing participants’ identities as capable students, problem-solving, and providing a safe place to express fears. Results indicated that students felt supported, were more comfortable in academically challenging situations, and experienced improved performance.

Despite attempts to address disparities in education through group counseling, some challenges remain. One specific documented area of concern was student perception of unpleasant administrator/teacher attitudes toward African American students (Bruce et al., 2009). Research shows that African American students with higher quality student–teacher relationships scored higher on achievement tests compared to African American students with lower quality relationships (Burchinal, Peisner-Feinberg, Pianta, & Howes, 2002). For this population, connectedness was essential in improving academic self-concept and social/emotional development, both of which were factors in increased school engagement and success (Moore McBride, Chung, & Robertson, 2016). Connectedness through mentorship has been identified as a key component of social/emotional development and improved student success among African American boys.

Connectedness through mentorship has been identified as a key component of social/emotional development and improved student success among African American boys.

Wyatt’s (2009) intervention showed that a male mentoring group improved student academic achievement and fostered social/emotional growth. Development in these areas may have ignited a sense of mattering and nurtured feelings of importance. Tucker, Dixon, and Griddine (2010) defined mattering as a psychosocial experience of feeling significant to others that contributed to students’ school success. Their research demonstrated that a sense of mattering led to feelings of confidence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation, which positively impacted academic performance of African American students.

Although the literature provides resources to support school counselors implementing group counseling interventions, much of this information does not offer practical strategies specifically targeted for use with African American boys. Resources outlining specific interventions for African American boys are needed to support counselors in their work (Miranda et al., 2007). The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of a group intervention for African American boys exhibiting at-risk behavior. The school counselor utilized data to implement a group designed to promote cultural identity and develop social/emotional skills while exploring postsecondary preparation.

The school in this study served Grades 6–8, with a total of 1,023 students. This middle school was located in a suburban area of middle Tennessee. Forty percent of the students were military dependents, and 47% received free/reduced lunch. Twelve percent of the students received special education services, and 3% received English as a second language services. The student population was diverse: 39% African American, 38% White, 17% Hispanic, 4% Asian, 1% Native American, and 2% other. The faculty and staff population was significantly less diverse, with a racial composition of 81% White, 15% African American, and 4% Asian.

Unique aspects of the school presented both strengths and challenges. Students were supported by three principals and two school counselors. One particular strength was the collaborative relationship between the school administrators and school counselors. The team approach allowed for consistent communication and dialogue regarding student need. The team also solicited input from students, teachers, and parents. Another strength was the implementation of a comprehensive school counseling program, which focused on students’ academic, career, and social/emotional development. The counselors were very intentional in delivery of services and used data to inform practice.

One particular challenge was the transient nature of the school’s population. Students enrolled and withdrew on a frequent basis, which made the process of relationship building more difficult. This was largely, but not solely, due to the high number of military families.

Although multiple factors influenced behavior and academic performance, a major belief of the administrators and counselors of this school was that positive relationships paired with skill development interventions potentially could reduce the discipline rate and affect academic achievement. The transient population did pose some difficulties, but regular reviews of data revealed opportunities for growth. Student observations also clearly demonstrated some areas of need. The combination of data and observations identified a high rate of discipline incidences from African American boys in general, with the majority of those receiving referrals in eighth grade. As a result, the school counseling team established the following goal to address this concern: By May 2016, eighth-grade boys with 10 or more discipline referrals in the first quarter will decrease referrals by 25% in the last quarter. A quarter was defined as a 9-week period. To accomplish this goal, the school counselor developed a group for African American eighth-grade boys who were identified through school discipline data.

Method

Group Leader/Participants

The school counselor served as the group leader and primary researcher for this study. She is an African American woman in her early 30s who holds a master’s degree in school counseling and doctorate in counselor education supervision. Her experience included 8 years of school counseling at the middle-school level and 3 years at the elementary level. The school counselor had experience with implementation of group counseling interventions at both academic levels.

The participants were eight African American eighth-grade boys. A review of school discipline data from the first quarter revealed that this particular subgroup obtained the majority of the discipline referrals compared to other subgroups within the school population. During the first quarter, African Americans received 60% of the discipline referrals compared to other ethnicities (White 30%, Hispanic 0.08%, Native American 0.01%, Asian 0.01%). Students in the eighth grade accounted for 50% of the discipline referrals compared to the other grade levels (sixth grade 23%, seventh grade 27%). Males acquired 76% of referrals and females acquired 24%. Potential group members were recruited based on ethnicity, grade level, and documented discipline infractions. Parents completed consent forms, and students assented to participate in the group.

Study Design

The goal of this practitioner research was to examine the impact of a group intervention for African American boys exhibiting at-risk behavior. The approach used in this research to examine the effectiveness of the intervention included descriptive statistics and pre-/post data analysis. We also used discipline rates, grades, and group member perceptions.

The purpose of the pre/post survey utilized in this study was to assess student perceptions of the 12 indicators (see Table 1). The survey indicators were based on topics that the school counselor presented school-wide annually. The pre- and post-group intervention surveys were created by the school counselor using the ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors for Student Success (ASCA, 2014) as a foundation. Scholars promote the use of ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors as a culturally alert responsive services strategy (ASCA, 2014; Schellenberg & Grothaus, 2011). Previous research, as cited in the literature review section, served as a groundwork for the development of the survey instrument (see Appendix A). The survey was designed as a 5-point, Likert-type scale with choices ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Example questions included: “I understand the importance of goal setting and know how to set appropriate goals” and “I use time-management, organizational, and study skills.”

Table 1. Pre-/Postintervention Assessment.

Procedure

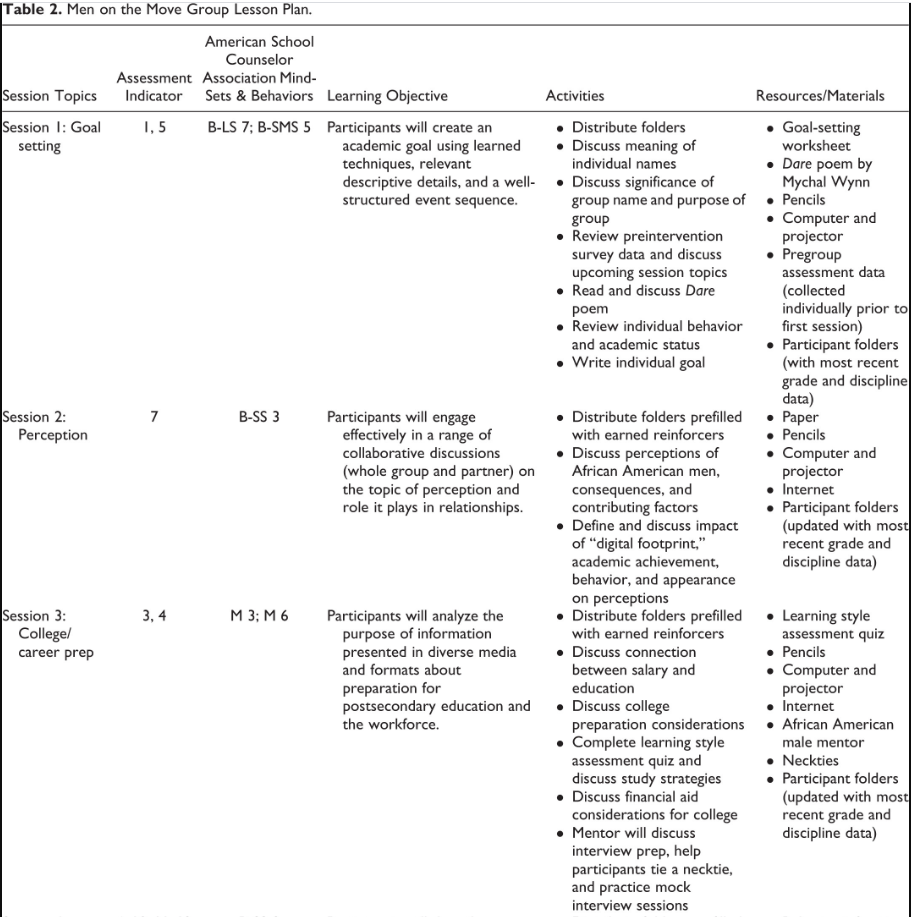

The school counselor worked to cultivate relationships throughout the school year. These efforts allowed authentic promotion of the group. The group was presented in a positive light and as an opportunity for growth. Students were invited to participate but had the option to decline. The name of the group, “Men on the Move,” was also intentionally chosen to establish a positive identity. The 6-week intervention took place during the third quarter of the school year in a nonacademic period, with sessions lasting 40 min. Upon receipt of parental permission, students participated in a pregroup meeting where they completed an assent form and the pregroup survey and discussed group expectations. Administrators approved the group and teachers were informed of days and times of meetings. Sessions focused on the following topics: goal setting, perceptions of self and others, college and career prep, responsibility, and preparing for success. Sessions included presentations by the school counselor, African American male guest speakers, group discussions, and activities that included resume development and sample scholarship application practice. Group discussions incorporated the complexities of the African American male experience, and resources and materials used mirrored the culture of group participants.

Group discussions incorporated the complexities of the African American male experience, and resources and materials used mirrored the culture of group participants.

Each group member was given a folder that was updated weekly with information on the current session, current grades, and current discipline report. Participants received weekly reinforcers called “Coyote Cash,” a type of incentive from the school-wide behavior support program. For the purposes of this intervention, participants received one reinforcer for each of the identified areas of improvement (grades and/or discipline).

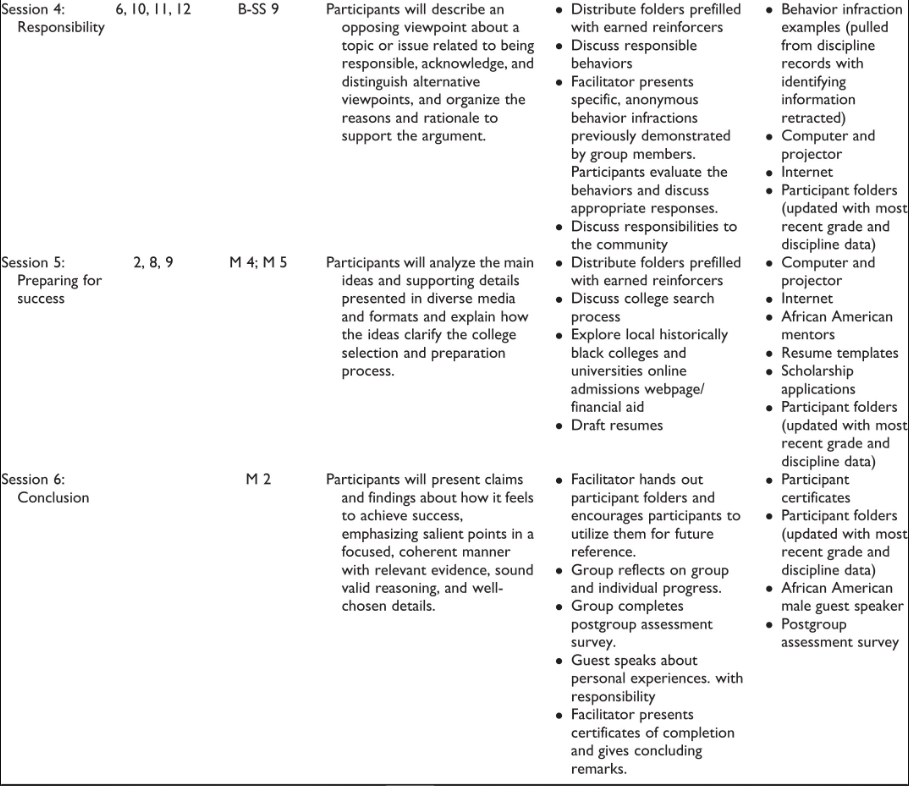

Group Intervention

This group intervention focused on three goals: (a) to improve student behavior, (b) to promote cultural identity and social/emotional skill development, and (c) to assist students in making relevant connections in preparation for postsecondary education. Table 2 presents the complete lesson plan. Prior to the first session, participants completed the pregroup intervention survey. In the initial session, the group leader reiterated the purpose and expectations of the group, and participants set long- and short-term goals. Participants discussed current standings and potential challenges to progress. These activities aligned with ASCA Mindsets & Behaviors B-LS 7 and B-SMS 5 and with Questions 1 and 5 on the assessment. During the second session, the group leader facilitated a discussion on perceptions of self and others. Participants explored cultural considerations as they discussed implications of minority group membership and threats to achievement. Participants also discussed potential contributing factors that reinforce negative stereotypes. These activities aligned with ASCA Behavior B-SS 3 and Question 7 on the assessment. An African American male guest spoke during the third session, addressing college/career preparation, interviewing skills, and dressing for success. The group leader presented information to promote college/career readiness. Participants also completed a learning style assessment. These activities aligned with ASCA Mindsets M 3 and M 6, in conjunction with Questions 3 and 4 on the assessment. In the fourth session, the group leader facilitated a discussion on decision-making skills using anonymous member behavior referral data. Participants shared alternative solutions and discussed responsibility. These activities aligned with ASCA Behavior B-SS 9 and Questions 6, 10, 11, and 12 on the assessment. The fifth session included a focus on academic and career success. Participants completed mock scholarship applications and resumes. These tasks reflect ASCA Mindsets M 4 and M 5 and Questions 2, 8, and 9 on the assessment. Another African American male guest speaker participated in the sixth and final session. The guest speaker shared his personal success story and provided words of wisdom and encouragement. Group members reflected on personal progress and on the group experience. At the conclusion of the group, participants completed the postgroup intervention survey, received a certificate of completion, and were encouraged to frequently refer to accumulated resources for support. A summary of the group outcomes was shared with administrators, teachers, and parents. As a postgroup follow-up, the school counselor collaborated with school staff to implement individual check-ins with participants to ensure continuous improvement.

Data Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to analyze discipline data and grade data and to compare survey items with pre-/postintervention group averages. Discipline referral rates were reviewed for each student on a weekly basis via the online discipline database. The school counselor documented the rate of discipline infractions for each participant and for the overall group. Grades were downloaded and recorded to track individual and group academic progress on a weekly basis using the student information system.

Results

During the first quarter, group members acquired 38 discipline referrals. In the final quarter, participants received 10 discipline referrals, a 73.68% decrease in overall group average rate of discipline referrals earned (see Table 3). Postintervention perception surveys garnered mixed results on self-reported skills for success. The following areas indicated a positive rate of change: steps for success (15.38%), college preparation (11.11%), career prep (12.5%), documenting accomplishments (15.38%), positive attitude (2.33%), time management (17.65%), and self-discipline (8.57%). The following areas indicated a negative rate of change: goal setting (−2.17%), effective habits (−5%), and importance of postsecondary education (−13.04%). No change was reported on working toward goals or positive recommendation letters (see Table 3). Small mean improvements in grades were noted specifically in the areas of English (+2%), Math (+6%), and Social Studies (+3%; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pre-/post grade average.

Discussion

This study focused on African American boys who acquired a higher rate of discipline referrals compared to peers. Upon completion of the intervention, a comparison between the preintervention and postintervention group discipline referral data indicated that the average rate at which the group received discipline referrals decreased. The decrease in discipline referrals may have been influenced in part by the specific focus on establishing trusting relationships throughout group sessions. This focus encompassed meaningful dialogue and positive interactions between group leader and participants. This result supported the previous assertion that African American boys demonstrate improvement in social/emotional skill development once they experience a sense of mattering.

The decrease in discipline referrals…supported the previous assertion that African American boys demonstrate improvement in social/emotional skill development once they experience a sense of mattering.

Other indicators that reflected a postintervention increase were the group average items related to steps for success, positive attitude, time management, and self-discipline. Dialogues centered on identifying environmental and cultural factors that may have served as barriers to success. The use of African American men as guest speakers provided models of success that participants could relate to. The match between gender/cultural background allowed participants to make connections during discussions. The group activities were intentionally designed to be culturally responsive; therefore, results may have been related to the intentionality and method of delivery.

Although a decrease was indicated in goal setting, effective habits, and importance of postsecondary education, participants reported that they enjoyed participating in all of the group activities. An explanation for these results could be that participants did not fully understand the complexities of goal setting and effective habits for success prior to the group and overestimated their position. Respondents also may not have adequately understood the term postsecondary when initially completing the assessment. Although postsecondary preparation activities were integrated into sessions, they were not labeled as such to participants, which may have given participants some difficulty in making that connection. Survey questions may have lacked clarity in connection to topics covered in the group. Leaders of a future implementation could consider creating explicit survey questions that clearly mirror group content; this might result in higher rates of change.

Participants reported no change on working toward goals or the belief that teachers perceived them positively, and the students verbally acknowledged the continued need for growth in these areas. Despite these data, an improved collaborative culture appeared to exist among the participants, school counselor, teachers, and administrators. For example, with teachers and administrators aware of who was participating in the group, they initiated more frequent collaboration when concerns arose regarding those students. This increased collaboration, although it was an unexpected consequence, proved to be beneficial for all stakeholders as areas of concern were quickly addressed and resolved. Participants also expressed a sense of belonging during the group process, which may have contributed to an enhanced sense of mattering. This sense of mattering may have impacted school connectedness.

Similar to the findings of Davis, Davis, and Mobley (2013), participants also seemed to benefit from a community of achievement. Although academic achievement was not the major focus of this intervention, improvements were noted. These results might be attributed to the realization that school success is affected by effort exerted and attitude toward work. Participants may have experienced a sense of mattering due to the frequent and individualized check-ins.

This study’s findings indicated an overall success of the group intervention. However, students may further benefit from intervention periods that last longer than six sessions. An increased time span could be used to explore presented concepts on a deeper level.

Implications

School counselors may utilize this group intervention model with African American students at their school. The use of data was especially beneficial in this study; therefore, school counselors may want to consider the consistent use of data-informed and intentional interventions. One approach might be the periodic review and disaggregation of academic and discipline data leading to the identification of gaps and implementation of interventions.

Although this study focused on one school in particular, the disproportionate rate of African American disciplinary issues is well noted in the literature (McKenna, 2013; Taylor & Brown, 2013; Vincent & Tobin, 2012) and, as previously stated, behavior is linked to academics. Historical practices reflect the melting pot perspective of the “one approach fits all” model, yet data indicate that this is not effective (Taylor & Brown, 2013). Such data demonstrate a need for more multicultural competency training for school employees. School districts could seek ways to evolve from a color-blind perspective to cultivate a culture of awareness and appreciation. Culturally responsive approaches require educators to not only comprehend student culture but to infuse it into class curriculum and activities. School counselors can be particularly helpful in development of this area and are expected to do so as stated in the ASCA (2019) School Counselor Professional Standards & Competencies (B-PF 6e). Through involvement in collaborative spaces such as school leadership teams and content area teams, school counselors can play an active role in curriculum decision-making. School counselors also can have a direct impact on infusing content with cultural relevance through cross-curricular lesson planning and integration with counseling lessons. The benefit of this approach was reflected in a similar strategy utilized by Schellenberg and Grothaus (2011). The researchers supported academic growth through the use of standard blending, which involved the inclusion of student experiences within the framework of a lesson to help students connect to the content of the curriculum. Researchers found that this strategy enhanced the achievement of competencies and student motivation.

Culturally responsive approaches require educators to not only comprehend student culture but to infuse it into class curriculum and activities. School counselors can be particularly helpful in development of this area and are expected to do so.

School counselors can add other components to this experience to enhance the impact on students. For example, the consistent use of African American male mentors may prove to be advantageous. Research posits that African American students experienced a sense of mattering as a result of meaningful relationships (Tucker, Dixon, & Griddine, 2010). The intervention in the present study used African American male guest speakers periodically, but a more consistent presence might provide an added layer of supportive involvement. Other supplemental activities to consider include college trips and increased family engagement.

School counselor education programs stress the importance of multicultural competence as essential to effective practice. The Ethical Standards for School Counselor Education Faculty (ASCA, 2018) emphasizes a curriculum designed to prepare school counselors in training to work with a diverse population. Future directions could include the creation of training opportunities that might lead to development of success strategies for marginalized groups. School counselors in training may particularly benefit by creating and appropriately applying culturally relevant interventions. They may develop these skills via service-learning opportunities and experiential courses and exercises.

Conclusion

This study adds to the existing body of research that examines the impact of specific interventions for African American boys. The techniques presented may reinforce both a sense of mattering among African American boys and the development of social/emotional skills. These factors also may serve to bridge gaps compared to other groups. Future research may seek to study the impact of collaboration. During this intervention, the school counselor observed that faculty reached out to her more often concerning group members. The implications of this research could be used to inform school counselor practice. The benefits school counselors gain can be passed along to schools in the form of more effective services because knowledgeable school counselors are better equipped to provide relevant interventions. Counselor educators and school districts could also utilize this information in the training of university students and school employees.